Leo Thompson MA, MEd is dedicated to empowering people to learn and grow through applied education research and innovation. Committed to global citizenship, Leo has a deep appreciation for different cultures and often visits schools internationally to appreciate their strengths and support their continuous journey towards excellence in their context. A former teacher and school head, he is now an independent education consultant, writer and speaker who lives in Vienna, Austria. For Leo, being successful must mean bringing sustainable value and well-being to the world in whatever you do.

“Schools don’t play the role they could in gearing up students for higher education. The curriculum pattern in the school system is mostly confined to bookish resources with an emphasis on exams. Therefore, students are not prepared for the original thinking demanded at university level.”— Lubhna Dongre, age 21, Indian university graduate and author.

We know that each year millions of students globally walk through the gates of a university for the first time. This hallowed ground is the next chapter of their education and life. But are they fully prepared for it? And if not why?

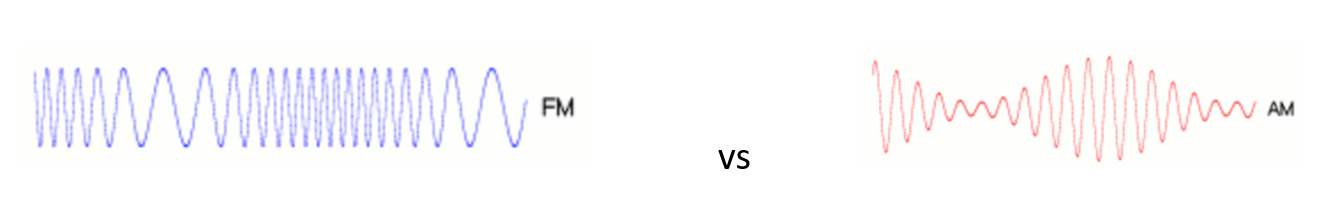

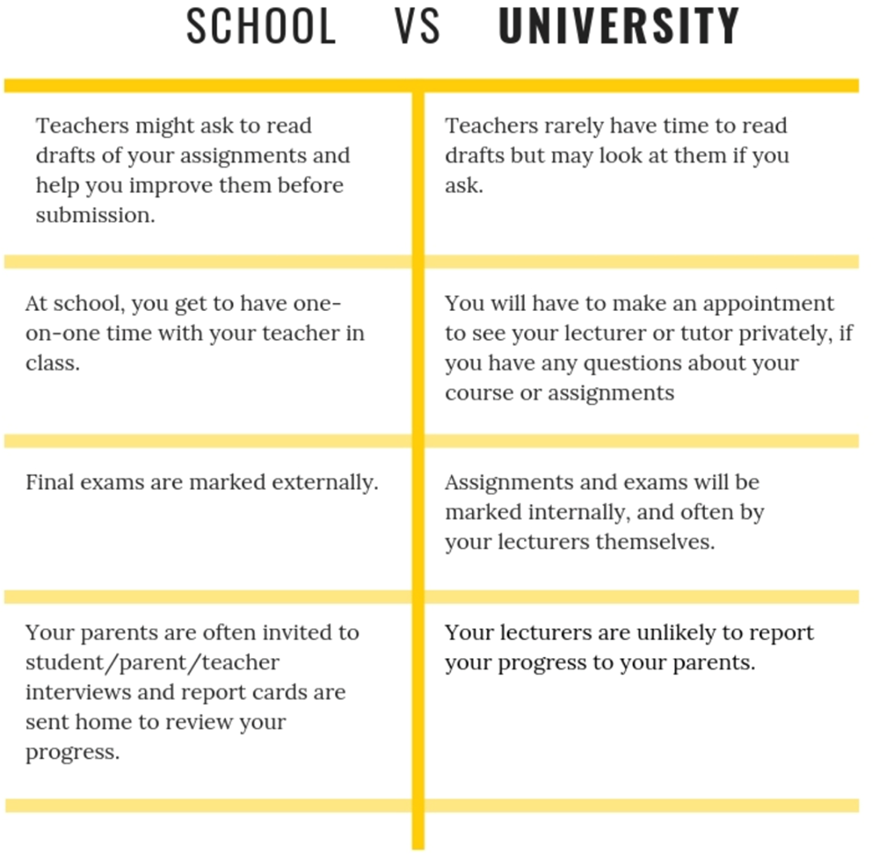

We also know that ending formal education to enter tertiary education is a major step in life’s path towards work for these students. Yet, it is like a change in radio frequency. School’s run on FM, universities run on AM. Let me explain with simple images and a table below. Interviewed students, just like Lubhna who will feature more in this article, are saying the same about the gulf in expectations.

The radio frequency is an analogy I would choose as schools and universities typically work differently when it comes to three learning specific areas.

- The level of learning independence required

- The volume of information/content that must be learned and understood

- The level of higher order thinking (see Bloom) required to be successful

To illustrate:

Though the dynamic is gradually changing, the traditional school model has been:

The curriculum is set ⇒ teachers instruct ⇒ student learns (dependently)

Though it is also evolving, the traditional university model has been:

The learning outcomes are set ⇒ lecturers facilitate ⇒ students learn (independently)

Getting harder!

Yes, typically students are expected to read, learn, and apply much more content at the university level than they did in high school. This is because university courses are intentionally more advanced and specialized than high school courses, and they often cover a wider range of topics with much more independent reading required. The volume of content is accelerating.

To this end, Dr Justin Sung, head of learning at iCanStudy depicts the scale and implications of the problem in a recent Monash University published article that “students often fail to finish the required amount of reading, especially when assignments and examinations are imminent; Zeivots found that up to 80% don’t complete their assigned readings.”

In addition to learning more complex content, university students are also often expected to learn how to think critically and independently, engage in deep analysis and research, and to communicate their ideas effectively. These skills can help students to be successful in their university studies and in their future careers. So, let’s revert back to the topic of who is responsible to teach students the skills they need and what services universities currently offer.

How do universities try to support new arrivals?

If anything, universities use a more flipped classroom model and schools typically use a more traditional model. In the flipped model, students are expected to be independent, motivated, high order, self-regulated thinkers and doers. The student must hit the books (read up) outside the baseline lectures and follow up discussion seminars that are used to introduce and consolidate the material and content.

The pursuant end of module, or end of year, exams can be on anything within the designated reading materials, which can be very broad and deep. Universities realise that students come from a variety of backgrounds and hence levels of preparedness and try to give them some essential skills as part of an academic support programme (sometimes known as an ASP). This is well intentioned but is it enough?

The limits of University Academic Support Programmes

Academic support programs at universities typically offer a range of services and resources designed to help students succeed in their studies. These programs may include research skills, citation, tutoring, writing centres, study skills workshops, and other types of academic assistance. They may also offer support for students with learning differences or disabilities, such as providing accommodations or specialized services.

In addition to providing direct academic support, academic support programs may also offer resources and advice to help students manage their time, set goals, and stay on track with their studies. Overall, the goal of academic support programs is to help students to be successful in their university courses and to reach their academic potential. These are no doubt helpful to many but may be a Band-Aid (superficial) solution with so much content to cover and at such a high level. The main skill of learning to learn independently seems to be missing.

Very varying levels of learning to learn components in schools

It depends on the school and the specific curriculum that is being taught. Some schools may place a greater emphasis on teaching students how to learn and develop critical thinking skills, while others may focus more on teaching specific subjects and content. In general, however, many schools or education systems do not adequately prepare students for the demands of university-level learning. Consequently, students need to develop additional skills and strategies to be successful in their university studies. Having talked to many of my former students and alumni who have ventured to university, most comment on the explosion in content volume, difficulty and independence required.

Again, Lubhna Dongre commented, “the student is generally required to fight their way through school and university facing academic and peer challenges with social expectations towards future studies or employment.”

Building a bridge between phases of learning

Learning how to learn is an important skill that will help students throughout their entire lives, not just during schools and college. Teaching students how to learn can help them to become more independent, self-aware, metacognitive, self-motivated, confident and efficient learners, will ultimately lead to better academic performance and a more successful college experience. Additionally, teaching students how to learn before they go to college can help to prepare them for the unique challenges and demands of higher education as well as help to set them up for success in their future careers. It builds a bridge between school, university, and life in general.

Diffused responsibility?

The Diffused Responsibility theory or phenomenon usually applies to situations where there are many people witnessing a disturbing incident where someone needs help and yet nobody acts. This theory can also be borrowed and applied to schools and universities. Is it the student’s responsibility to take learning ownership when they do not know how? Is it the parents’ responsibility to instil skills in their child when they do not know how? Is it the school’s responsibility when they have partial knowledge of learn to learn? Or is it the university’s responsibility? To a degree, perhaps ownership should be shared by the most informed and universities and schools should give much greater attention to ‘learning to learn’. Imagine the possibilities if every child and every student had access to this life tool and their parents encouraged it?

Michael Tsai – Cofounder of iCanStudy who are aiming to revolutionise learning to learn by building a 100% research driven integrated system to empower humans – commented on the shortfall in education that schools and universities globally have not yet addressed despite positive intent:

“A metaphor for the current situation is that you have a fully equipped kitchen, but without a recipe and skills training you cannot use it to the full capacity. Learning to learn is the only really sustainable solution for students at all ages in the hyper information age.”

To wrap up, an alma mater can be translated from Latin to ‘Kind Mother’. Universities are indeed wonderful institutions.

However, to continue with the analogy the mother could be even more kind by focusing on learning to learn by way of teaching students an integrated system within the universities’ academic support programmes. This will help the mental health of the students, amongst other win/win benefits.

…and, as Lubhna suggests, schools and universities should both take responsibility for this. Then students will be both AM and FM ready.