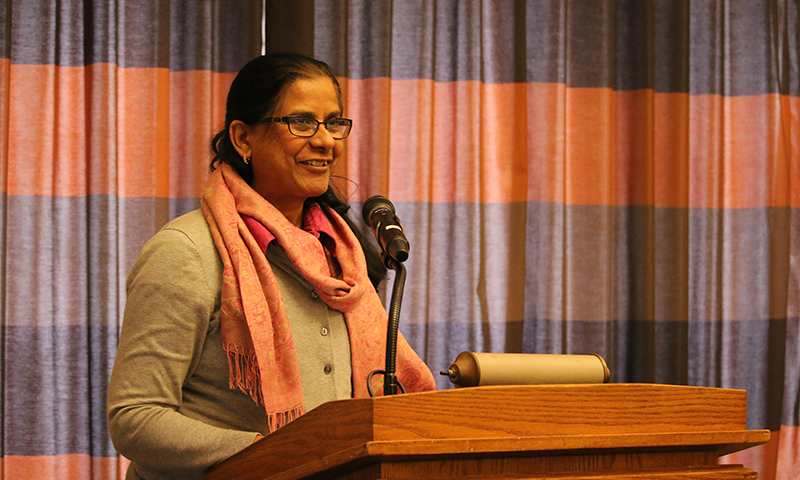

Mangala Subramaniam is Professor of Sociology and Butler Chair and Director of the Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for Leadership Excellence at Purdue University, West Lafayette (U.S.A.). In her current administrative role, she focuses on providing opportunities to enhance leadership skills and professional development for faculty. The key initiatives she has created for faculty success includes the Coaching and Resource Network for assistant and associate professors and the Support Circle as a culture of care network which serves as an informal, flexible support initiative for faculty. Her keen ability to be inclusive of various constituencies on campus has led to great success of the Center’s initiatives. Professor Subramaniam is currently working on a co-edited volume on leadership in higher education. Her co-authored piece in Inside Higher Ed (July 2020) provides recommendations for advancing women to leadership positions. This is reflective of her expanded research interests in the areas of gender and leadership, careers in the academy, and inclusive excellence. She is the current State Co-Director of the American Council on Education (ACE) Women’s Network of Indiana and was an Associate Editor of Social Problems which is one of the top four journals in sociology.

Do you think women in leadership roles are still a minority? What is the situation in the higher education space? How can we increase the number of women in leadership roles?

Yes, women are still in the minority in higher education leadership, particularly so in what we refer to as doctoral institutions which are also referred to as research intensive or R-1 institutions in higher education in the U.S. The trend is similar across countries as I noted in my keynote at the GEARING Roles’ second annual conference, Gender and Leadership in Higher Education and Research, (Consortium of Universities across 8 countries of European Union including UK) in November 2020. Let me address three aspects in response to the first two questions and then provide some suggestions to increase the number of women.

First, in the U.S. typically full professors are considered for major leadership positions (although few positions may be non-faculty positions, that is filled as staff positions). As per the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) 2020 report, representation of women among full-time tenure line faculty members decreases with progression in rank (assistant to associate to full). There are disparities in the representation of women among full-time tenured or tenure-track faculty members within higher academic ranks. Nationally, 32.5 percent of full professors are women. But underrepresentation is particularly pronounced among the Hispanic or Latino and Black or African American categories.

Second, the leadership data mirror somewhat that of faculty. Women hold the least senior administrative positions and are the lowest paid among higher ed administrators. The picture is starker for women of color: in 2016, only 14 percent of higher ed administrators — men and women — were racial or ethnic minorities. Gender intersects with race in higher education: 86 percent of administrators are white, while only 7 percent are Black, 2 percent Asian and 3 percent Latinx. Less than a third of college or university presidents have been women, and the majority of them have been white women. Not surprisingly, among faculty members, white men make up the largest numbers of people in senior positions, and in recent years, white women have made significantly more gains than women of color. According to a new study from Eos Foundation’s Women’s Power Gap Initiative, the American Association of University Women and the WAGE project, women represent just 24 percent of the highest-paid faculty members and administrators at 130 leading research universities. Women of color are even more grossly underrepresented, at just 2 percent of top core academic earners. One of the most surprising statistics is the minimal number of Asian women among the top earners – just 3 women (note Asian in the U.S. includes South Asia). This is despite women being 60 percent of all professionals in higher education and earning the majority of master’s and doctoral degrees for decades in the U.S. Perhaps, bias in assessing accomplishments and in enabling opportunities is playing a role.

More recently, women have been appointed as presidents in a couple of high-profile female university presidential appointments among Research-1 (or Tier 1) institutions. Perhaps, opportunities will open for women and for women of color following the recent protests for racial justice as well as the election of the first woman of color Vice President in the U.S.

Intentional efforts are needed to build a leadership pipeline for opening opportunities for women and women of color. We need to challenge not only gender, but racial/ethnic stereotypes.

Investing in women and women of color with potential by providing resources to attend relevant professional development programs can facilitate creation of a pool. Mentoring – formal and informal – and role models for women can help. As Barres in his article, Does gender matter? in the journal Nature notes, “… a great deal of hallway mentoring that goes on for young men that I am not sure many women and minorities receive.” I would extend the reference to ‘hallway’ mentoring to an informal component of mentoring that may be tapped from networks that women of color are rarely a part of. Such networks may be useful for navigating difficult work terrains that are less about expertise. Perhaps women of color are less likely to be even considered for leadership positions because they are not part of powerful networks or cliques (of both men and women).

One potential strategy for universities to pursue is to ensure open search or hiring processes which often seem to be bypassed entirely for top leadership positions when it matters most. Such searches must seriously consider candidates beyond those appointed in the interim or acting position. Another possibility is consciously affirming the accomplishments and constructive work of especially women of color leaders as they are less likely to have advocates in existing networks or cliques. This will also go a long way in building confidence and credibility. I cannot emphasize enough here that what is not stated (accomplishments) is as important as what is. In making leadership search opportunities open, the inclusion of a lone woman of color in a hiring committee is often assumed to meet the creation of a diverse search committee. That is tokenism! Moreover, the lone of woman of color is rarely heard and is more likely to vote differently than the rest of the committee. Maybe a diverse committee is having up to 50% or more faculty members of color in a committee. While this may add a service burden especially for women of color, they could be compensated in other ways, including no other service for that semester or academic year. [By women of color I mean women of African, Caribbean, Asian, and Latin American descent, and native peoples of the US and include those of dark skin color.

Why is gender balance and having a more diverse workforce necessary, especially in senior management teams?

Gender balance is key for ensuring excellence. I (with my co-author) lay out some imperatives in a 2020 column. In there, we note that there is an ethical and antiracist imperative as well as a business imperative. And I quote from the column, “Achieving gender parity in leadership is, first and perhaps most important, a matter of fairness. When women are excluded from top leadership positions, they are denied the agency to make a difference in their workplaces and societies. Leaders enjoy power, high status and privilege, and leadership in one area opens doors to other opportunities, which further amplify the perks of leadership.”

Evidence from a 2018 report shows that companies have improved profitability when diverse women are in leadership positions. Companies which shifted from a leadership structure of no women to 30 percent women had a 15 percent increase in profitability. Conversely, companies in the bottom quartile for both gender and ethnic/cultural diversity were 29 percent less likely to achieve above-average profitability.

A diverse senior leadership team can enable bringing in a wide variety of perspectives into decision-making. For instance, in higher education, experiences differ, and challenges encountered vary not only by gender, but also by race/ethnicity, socio-economic status, and immigrant status (as well as other differences). Integrating and incorporating these perspectives into discussions can be critical for inclusion and success. It allows for understanding the range of experiences rather than create hierarchies (such as hierarchies of privilege or oppression). Consider for example, the disruptions due to COVD and discussions of carework being narrowed to childcare (which is needed), despite the scholarship during the past year or so calling for broadening the notion of care work to include child care as well as selfcare, elderly care and so on. Leaders in positions of authority, either because they choose to ignore or are unaware, reinforce the narrow version of carework and/or convey a hierarchy of those. In doing so, they erase the range of work and those who engage in that work who may all be affected by the pandemic. In the higher education arena, these aspects have consequences for how faculty members may be assessed and rewarded as part of the annual review process in the current context of the pandemic. Understanding the varying experiences combined with topical knowledge/expertise is key for leaders; it is not only about having the ‘right’ temperament for a leadership position as women of color are often told!

What are some of the factors or obstacles that deter women from actively pursuing leadership roles?

I will discuss some major barriers that women and women of color face, particularly in higher education. One is underrepresentation. As I noted above, women, and especially those of color, are underrepresented in tenured and full professorships that in turn limits opportunities to advance into formal leadership positions at colleges and universities. Yet we know, from research and my own academic experience, that qualified and ambitious women are definitely not in short supply.

Second, opportunities disappear along the way. Women are not simply denied top leadership opportunities at the culmination of a long career, but rather such opportunities seem to disappear at various points along their trajectories. And even when women attain leadership positions, we face challenges at the institutional and individual level – such as individual mind-sets – which need change.

Third, deep-seated networks open leadership opportunities for some faculty members but usually for men. Women’s networks lack power as they are less likely to occupy positions of authority. And women of color are often isolated as there are few women of color in leadership positions. The exclusion of women and women of color from top leadership denies them the power to initiate and implement change. Additionally, gender and racial stereotypes such as expectations that women be deferential, not assertive or confident in expertise is often the norm. The stereotypes are embedded in systems and within institutions and it will require deliberate and conscious efforts by all of us to enable transformative change. Stereotypes and biases present subtle yet significant obstacles for women and women of color. At the same time, when women are required to fit into tightly defined feminine roles to be accepted, those who are willing to act as expected often end up in opposition to those who aren’t. Women who behave in traditionally feminine ways may find women who behave in traditionally masculine ways off-putting, and vice versa. In this way, gender bias can create conflict among women. So, professional women who have succeeded by playing by men’s rules may have a lot invested in proving that ‘that’s what it takes to be a serious professional.’ Women who seek to change the old rules may be dismayed and disappointed when established professional women don’t support them.

Finally, let me also point out that recognition and rewards can be a stumbling block for women doing leadership work. Perceptions of performance, the ability to highlight them through networks, particularly what is not mentioned or not recognized (remain hidden) are powerful influencers of success. While a few leaders acknowledge accomplishments, many others adopt the ‘non-mention’ strategy or diminish its importance by referencing others works as being equally important as if there is a need for an equalizer when it comes to women of color. I can think of several experiences, related to the latter, in my career. The non-mention strategy is a hidden hurdle for women of color in mid-level leadership positions. The lack of advocates also leads to invisibility.

When looking specifically at educational planning and management, why is it essential to have women in leadership positions?

In response to this question, I would reiterate much of what I have noted above. Women bring perspectives based on their own experiences and can contribute to understanding potential and excellence as different than the dominant normative in considering the many aspects of planning in higher ed – student, staff, and faculty related.

Diversifying a variety of top leadership positions is more than an initiative to level the playing field – it is about using the best resources to drive excellence – individually and institutionally.

Greater gender, and I would add racial/ethnic, diversity can translate to increased productivity, greater innovation, better products in terms of courses and students admitted and graduated, better and informed decision-making, and higher employee retention and satisfaction.

As a woman in a leadership position, what was this journey like for yourself? How were you able to overcome the different obstacles encountered?

Frankly, I had little knowledge of the challenges, mentioned above, when I entered academia as an assistant professor, soon after completing my PhD. Most of us starting on an academic position, think about being tenured and promoted first, that is moving from an untenured assistant professor position to a tenured associate professor position. This typically takes 6 years. And then the next step is becoming a full professor and as I noted above, proportion of women full professors is low (about 23% of full professors at Purdue are women).

I had never thought of an administrative or leadership position at the university level, although I’ve held some administrative positions at the department and college level (there are 13 colleges at Purdue). When I was invited to apply for the current position, I was initially hesitant. I was not part of influential networks at the university level, and added to that, I am a woman of color. And so, I was surprised to be offered the position. Accepting the position, I knew I would be wading through difficult waters. And I was conscious of being in a position of formal authority as I know from scholarship that women of color are less likely to be respected for their knowledge and opinions. In essence, I was not under any illusion that it was going to be straightforward or easy.

In my current role, as the Chair and Director of the Susan Bulkeley Butler Center for Leadership Excellence at Purdue University, I connect with faculty across campus, think about potential professional development needs, issues of diversity and inclusion on campus, particularly faculty, engage in inclusive listening, and try to build relations of trust with faculty.

I am about three and a half years in this position now and it has been exciting and challenging at the same time. Exciting because some of the new initiatives I’ve built have gained national attention and my work has been cited in high profile sources such as the Chronicle of Higher Education and covered in podcast interviews, such as in the series, In the Margins.

My experiences as an assistant and associate professor have deeply influenced and shaped some of the programs and long-term initiatives I have rolled out from the Center. For instance, the initiative for coaching and mentoring for faculty, called the Coaching and Resource Network, announced in Spring 2019 is designed specifically for assistant and associate professors to seek advice and have an advocate or sponsor outside of their department. It allows faculty members to address isolation, navigate work environments, and obtain counsel beyond those in their department. I created the Network under the quite well-established argument that improved work environments can raise productivity. The coaches are full professors – men and women with different racial/ethnic backgrounds and from across disciplines. Currently, there are about 40 assistants and associates participating in the initiative. This unique initiative is now being replicated at a couple of other universities. Similarly, recognizing that women typically stagnate at the associate professor rank, I started a conference for associate professors.

My academic journey has made me think more deeply about issues of inclusion and bias along gender and racial/ethnic lines. Inclusion is not mere representation, but integration and incorporation of voices into decision-making. But representation itself is complex considering the inter and intra group (marginalized groups) dynamics. I find that women are expected to conform to gendered norms – be nice, but not confident or assertive or serious about what they do or else they may be labeled aggressive or not nurturing or demanding excellence. Not adhering to stereotypes can prove costly. It is even hard to explain these different experiences to most leaders because being privileged they are unlikely to have had any such encounters.

I have also observed that marginalization of knowledge and expertise are not uncommon for women of color, and accomplishments are sometimes viewed with suspicion. I still recall a department head telling me, “you do not need to do so much.” I wondered if, as a woman of color, I was not expected to accomplish much although we know that we have to do twice as much to get half as far. I must note that as a graduate student and for most of my academic career, I have had predominantly male mentors.

I am not sure I can say that I have overcome all the obstacles. In fact, I am still learning to be resilient while knowing I am vulnerable. I consciously try to respond to challenges as opportunities, including doing research on those topics. At the Center, these include assessment of initiatives as well as documenting research through the Working Paper series that I started in 2018 and for which we accept abstracts from across the world. Additionally, we announced a book series, Navigating Careers in Higher Education through Purdue University Press that is open for submissions from scholars from across the world.

My interdisciplinary background, with each degree in a different discipline has been an asset. Additionally, as a woman of color, I tend to relate to the experiences of women and faculty of color, and as a social scientist I understand how intersections of difference shape power and privilege. My methodological skills prove very useful in designing research and examining and interpreting data as well as in being able to assess how data are used (or not) to make arguments.

I strongly believe that interactive, discussion-based education that raises awareness about key ideas of privilege – based on both gender and race, that is not only male but, white privilege, as well as their intersections – is essential for leaders and faculty. To this end, I have, through the Center, created and offered workshops about gender bias and intersectionality, how to engage in conversations about inclusion, and also hosted speakers from outside Purdue and workshops by external agencies. Some workshops/panels addressed key gendered academic issues such as service (committee) workloads and salary negotiation.

Being persistent and resilient, despite push-back, and staying focused to do what I believe is important to do has allowed me to pursue research and programs that are meaningful for faculty. My aim is to always ensure that the path to moving up the ranks and/or leadership for faculty, especially women and under-represented minorities, be relatively free of hurdles. I have always been candid and honest which is not the norm as compliance and deference is expected particularly from women. Moreover, the work of institutional transformation is not easy and nor is it possible to do it all alone.

The leadership programs I have attended have proven to be immensely useful, and the related networks continue to be a source of support. Additionally, having a successful woman leader who had served as a university president as a mentor has been helpful for even asking questions such as, am I being unreasonable in seeking change that hinders women of color from succeeding or am I expecting change too soon, or are my instincts about lack of recognition or inclusion relevant, and so on. I also believe that the initiatives and programs I envisioned and implemented successfully was because of the tremendous support from Purdue’s faculty and particularly from Purdue’s current Provost, Jay Akridge. I will remain ever grateful for that.

Overall, the journey over the past three and a half years has been a mix of excitement, opportunities to make positive contributions, as well as challenges that provided me with valuable lessons for navigating academic spaces.

Is there any disparity between the number of male and female Indian students studying in the US? How can we encourage more women to enroll in studies traditionally occupied by men?

In 2019-20, a little over 193,000 Indian students (about 18% of the total # of international students) in the U.S., only second to China. I don’t think there is much of a difference in the proportion of male and female students studying in the US. A greater proportion of students are likely to be in the pure sciences and engineering.

In both, India and the U.S., there is a need for women role models in the sciences and engineering so that female students can see what is possible. There is also an urgent need for women in leadership roles across levels within a university including elite institutions – full professors, department heads, deans, and university level administrators. Women not only need to be appointed to these positions, but also be treated with respect, as knowledgeable and as key contributors to decision making. This also requires intentional efforts on the part of institutions. I think this applies to most countries. For instance, in India it means directed efforts by the government and higher education overseeing bodies, such as the UGC. I would go so far as to say that the re-structuring of higher education as envisaged in India’s recent NEP misses some key aspects of access, equity, systems of recognition and rewards, and even leadership.

At the same time, it is not about educational institutions alone, we need an overall shift in societal gendered norms and stereotypes so that the abilities and skills of women and women of color are not differentially valued compared to men.

What is your advice to the female Indian students who wish to study in the US? How can they become successful by choosing US Universities as their higher education destination?

The current generation of students from India are a little different than the previous generations. I am speaking in reference to the general trend and acknowledging that it is not all students. The difference I mention has partly to do with what it means to be successful. While some students desire to achieve, there are many whose goal is to do the minimum and find a job that is realize the ‘American dream’ even if they do not frame it that way. My advice to the current generation of students is two-fold. First, at an individual level, to not succumb to peer pressure to conform, or believe in assimilation in ways that feel like a ‘new found freedom’ especially those who have led a ‘sheltered’ life before coming to the U.S. Additionally, it may be worth critically thinking about status hierarchies particularly race and ethnicity because students tend to perceive and respond to the new racial hierarchies in distinct and gendered ways.

In a broad sense, selecting a specific U.S. university may be driven by a variety of factors, ranging from discipline/topic of focus, funding, level of expectations by faculty. Major Research I universities in the U.S. do not differ in terms of focus and emphasis. Faculty members at these universities typically engage in major research and it is an opportunity for students to learn and excel, and it is going to involve hard work. The bottom line is what one expects about oneself – do the minimal required work and find a job or the desire to excel.

As an experienced academician, what would you like to change in the field of liberal arts education or our current higher education system in general?

Liberal arts education provides a strong foundation on topics that provide a basis for understanding society – understand the world you live in. Learning how social forces impact lives and shape experiences is key to understanding privilege and disadvantage. Difference based in gender, race, ethnicity, nationality, caste or body ability, and their intersections, can influence access to resources – education, health care and so on. Knowledge of these issues is particularly important in a globalizing world as we interact with and work with a wide variety of people.

I think there needs to be a greater recognition of the value of the liberal arts across the world. Liberal arts courses can provide key critical thinking and writing skills. Undergraduates in the U.S. are required to complete some core liberal arts courses. That I know is not uniform in India and nor are social science courses taken seriously by students particularly in the sciences and engineering. In most countries, there is a bias that science and technology/engineering is ‘good’ science and the social sciences is ‘easy and just talk.’ But in the U.S., social science includes training in rigorous and sophisticated methods of research and writing. It is typically evidence based; and I know that is different in other countries. Moreover, what we miss is that technology or technological solutions are based in societal relations built around privilege and disadvantage and access. Additionally, requiring social sciences in research grant projects can foster better solutions. We adopted such an approach with projects funded through a Mellon Foundation grant. It required a collaboration of faculty in the social sciences and the sciences, engineering, or agriculture. The principal investigator was required to be a social scientist. This model allowed for conversations across disciplines to address major global challenges. Such approaches will require intentional efforts. Therefore, resourcing social science disciplines and even creating interdisciplinary programs can go a long way in bettering education.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, what are the significant challenges for academic leaders? How did you manage the teaching at Purdue College of Liberal Arts without any severe hassles?

First, all institutions of higher education in the US and across the world have been faced with challenges. Leaders were managing the uncertainty and using information available to make decisions. Planning in uncertainty is tough and addressing the need of different constituencies – students (domestic, international), residence halls, staff, faculty including faculty who had traveled out of the country for research or were spending their sabbatical at a different institution or country.

It was in the immediate – middle of spring 2020 (March) – that how things will unfold was unknown. At Purdue, a task force was established, and regular weekly electronic updates were disseminated to campus (Protect Purdue).

Classes shifted to the virtual mode – some synchronous and some asynchronous. Service/experiential learning courses and lab-based classes had to be modified. Liberal arts courses were all shifted to a virtual mode. Additional instructions followed in terms of revising or dropping class participation points/grades and reassessing or reconfiguring exams and required assignments. Research by faculty was affected as labs were closed or had to operate within specific protocols, field based data collection within the U.S. and internationally was not possible, and collaborations were restricted to the virtual mode. At the same time, faculty members were scrambling to move their classes online. The shift to the virtual mode also brought to light class-based differences as some students had limited access to the internet.

This initial experience, in spring 2020, led to modifications for summer classes and the fall semester. Additional tech support was put in place for teaching. And in the fall semester (2020) some courses were in-person, but students had the option to attend or watch a recording. COVID testing protocols were developed and put in place. Vaccinations became available in early spring 2021. Purdue is now a vaccination site and that has enabled students to be vaccinated.

My focus is on faculty and so starting in April 2020, through the summer and this academic year (202-21) I listened to many faculty members who contacted me. It was not merely listening. As Purdue’s Provost reminded me later, I was engaging in intentional listening which may surface ideas for new resources and needs that a unit/organization is not yet addressing. The ‘listener’ may believe they have to solve the problem/issue which can prevent ‘listeners’ from engaging. In reality, the person who is looking for support wants to see their issues addressed so connecting this person to resources or recognizing the need for resources can be the most important action to take. In the context of the pandemic, everyone is stressed and that holds for faculty too. We are all dealing with uncertainty and so are the faculty. This intentional listening led me to develop two initiatives in the wake of COVID. One is the Support Circle and the second is the Best Practices Tools.

In fall 2020, I created and announced the SBBCLE-Support Circle as culture of care network and put together a list of resources within and outside Purdue. This care network is an informal, flexible support initiative for faculty during the crises. Open monthly ‘drop-in’ sessions have been organized. Six faculty members are involved as Faculty Allies – one is a co-chair with me. The drop-ins have become a space for sharing anxieties as well as potential strategies that may have worked for self-care, teaching, and research. The second initiative is the Best Practices Tools to document the impact of COVID on research and teaching which also is the basis for faculty annual review for assessing progress of particularly assistants and associates as well as annual raises. The Tools have received much attention nationally and several universities have accessed it.

I also used existing resources as a means of highlighting the experiences during the pandemic. For example, we had two volumes of a special issue of the Working Paper series focused on higher education and COVID. The existing Coaching and Resource Network had already established relations of trust and so proved to be useful.

There are also several university level initiatives for faculty. The Provost held regular forums with updates and addressed questions as we continued to deal with the pandemic. Other initiatives included an automatic one-year tenure clock extension for assistant professors and a plan for a recalibrated annual review and tenure and promotion process. A protocol for returning to research was developed for faculty. As the months progressed and we all experienced ‘virtual fatigue,’ guidelines for remote work were announced.

What projects or goals are you working on or leading currently?

One of my goals is to use both experiences/narratives and evidence (in the form of data) to consider best practices for faculty success. It can inform what leaders should do and how accountability and transparency can be built into structures, such as committees and processes of decision-making that will mitigate bias rooted in difference, particularly gender and race/ethnicity. These topics are central to my research and writing. Another key goal for me is to advise more faculty to focus on constructive relationships that will foster their productivity. That means mitigate conflicts and friction to the extent possible.

I’m currently working on a couple of papers, a book manuscript (monograph), and a study/project. The papers are focused on university responses to incidents of racism in the form of statements that may recognize one racial or ethnic group and erase others; and that has implications for inclusion and the approach of university leadership to pursue a holistic view (or not) of change. The monograph discusses an inclusive excellence framework for leaders. It relies on analysis of data that provides details of number of faculty members by gender and race in R-1 or doctoral institutions in the U.S. I discuss the ‘work’ of leadership – the hidden or invisible labor that cannot be tangibly measured and which many of us do – and strategies for institutions of higher education. In the long term, I am also very interested in comparing higher education institutions leadership patterns in India with that in the U.S.

A study about the experiences of faculty members – mentees and coaches – in the Coaching and Resource Network will commence this summer. I also have plans to develop an advanced module of a gender bias workshop in collaboration with three other faculty members. And I will, of course, be planning for what the Center will offer this upcoming fall. And of course, I will also keep an eye on what the post-vaccination world will allow.

Do you have any thoughts you would like to share about being a woman in the education sector or advice for other women carving a top management space?

Based on my experiences and as I continue to learn, I outline some suggestions for leaders. I suggest being persistent and seeking out role models; role models who you look up to, respect, and trust.

Being clear about expectations of leaders across layers below you in a hierarchy can ensure goals are met. As a leader, try to make space for others – don’t move up the ladder and pull it up with you! You can sponsor and mentor, that is you can be a better leader by investing in talented others (see Sylvia Hewlett’s book). Even informal mentoring can be useful as Ben Barres notes in his 2004 article, Does gender matter? in the journal, Nature. Barres says, “… great deal of hallway mentoring that goes on for young men that I am not sure many women and minorities receive.” Affirming the constructive work of especially women of color leaders can reinforce confidence and credibility. Professional development for leaders and others (such as faculty members in universities) is much needed. Building a pool of leaders to draw from would be useful in the long term.

Constantly challenge stereotypes – gender, age, ethnicity, among other differences. Be honest to yourself about what you want to see change. Being committed to diversity in all forms can foster excellence. It includes diverse representation in committees and incorporation of opinions into decisions. Balancing transparency while being mindful of confidentiality can go a long way in building relations of trust with colleagues.

Just knowing and being aware that there will always be some men and some White women who may minimize the successes or accomplishments of women of color faculty itself can soften the jolt if and when it happens. In essence, silence can be powerful as it may be about refraining to open yourself to subtle attacks. You can take a step back, recalibrate, and continue to pursue your goals.

Recognize and reward accomplishments consistently. Consider nominating those with potential for awards and programs – make it possible to consider those who may be hesitant or less likely to make a request to be nominated.

Improving the opportunities for women, particularly women of color, in universities or even in the corporate world, must be beyond their own institution or company. On strategy is to make women of color leaders visible. Make women of color the chairs of committees – the power and responsibility can convey commitment to diversity and excellence – and compensate them for that service work. When hiring women of color faculty, ensure that candidates meet women of color in leadership positions so that they know there are institutional sources of support if they were to be offered the position and accept it.

Finally, acknowledging the challenges but not letting it deter your focus is imperative to be able to excel. Yes, it is easier said than done!

Thank you for contacting me about this interview. I appreciate the opportunity to share my thoughts and hopefully contribute to the thinking of others. In conclusion, I would like to acknowledge Susan Butler and the Sheth and Ranade families for their endowments which make the work from the Center possible. To reiterate, I am grateful to the Provost for the opportunity to lead the Center and to the faculty members whose time and effort make the Center’s programs and initiatives possible.